Voters don’t have much information to go on when they decide the fate of judges on the last pages of their sprawling ballots.

This year, they’ll have even less information.

Finding information on the judges up for retention elections is a notoriously hard task.

Perhaps the best resource for voters is the reports the Arizona Commission on Judicial Performance Review releases before elections. The 34-member commission of attorneys, judges and citizens has access to information that voters don’t, and members recommend whether voters should allow a judge to stay on the bench.

Those recommendations, which say if a judge meets the commission’s performance standards, are made through a vote that’s historically been relayed to voters.

This year, voters won’t know the vote count detailing how many commission members thought a judge should be retained.

In November, 69 judges across the state face retention elections in which voters will decide if they deserve another term. The commission says they all met performance standards, and it recommended voters retain every judge this year.

Arizona is one of only six states that puts judges through a review process with a commission that provides reviews to voters.

Much of that review process, however, plays out behind closed doors. And the way the commission presents information has changed a lot since 2022. If voters took the time to look at the confusing tables in the commission’s reports for each judge, they probably wouldn’t learn much.

Instead, the only thing most voters see is whether the commission decided the judge met the standards or not.

Those decisions are especially important in this election, when voters will weigh in on the fate of two Supreme Court justices, four Court of Appeals judges, and 63 judges throughout Maricopa, Pima, Pinal and Coconino counties.1

This year alone, those judges have made rulings protecting the identity of election workers, declaring a controversial border proposition constitutional and upholding a near-total ban on abortions in Arizona.

Arizona Supreme Court Justices Clint Bolick and Kathryn King were part of reinstating that abortion ban, and now they’re facing a targeted campaign to remove them from the court this year.

Proposition 137 would end automatic retention elections for judges. Instead, voters would only get the opportunity to oust certain judges if the commission determines they haven’t met standards, or if they’re convicted of a felony or certain other criteria.

It’s retroactive, so If the measure passes, the results of November’s retention votes will be ignored. And given the commission consistently thinks all judges are pretty good, voters won’t have much ability to kick a judge off the bench in the future if the proposition passes.

Arizona made the official switch to retaining judges through a merit selection process, instead of electing them through partisan elections, in 1974. Sandra Day O'Connor championed the move while she was a state senator in the 1970s.

In the late 1990s, the commission started publishing a report detailing how members voted on whether each judge met standards.

But that changed this year.

In 2022, three judges lost their retention elections, making them the first in nearly a decade to get booted by voters. Only one of them, Judge Stephen Hopkins, didn’t meet the standards of the commission.

But the other two, Judge Rusty Crandell and Judge Howard Sukenic, had a few commissioners vote against them.

In the past, the majority of the commission’s votes were unanimous, but the public votes on the Secretary of State’s publicity pamphlet let voters know if there was some disagreement.

This year’s pamphlet doesn’t display the votes at all.

In fact, the commission placed all the judges that met standards on a consent agenda that was approved with a single voice vote, instead of having a roll call for each judge.

Commission Chair William Auther said that’s because the old pamphlet also included a third column besides yes-or-no votes to reflect members who didn’t vote or weren’t present to make one, and “groups on both sides of the political spectrum had chosen to weaponize abstentions in very inappropriate and untruthful ways” by implying they were votes against a judge.

Albert Klumpp, who did the first-ever doctoral dissertation on judicial retention elections and keeps track of the elections throughout the country, said he “very much doubts” absentations alone would lead to the shift away from transparency, especially given those with even a few votes against them were booted from the ballot last election.

“I'm not surprised that certain people would want the votes to be removed since they're seeing that the votes have an impact,” he said. “But it is public information, so I'm kind of surprised that that's not there anymore.”

Arizona’s judicial branch is ideally nonpolitical. But in practice, that’s almost impossible to pull off. Judges are appointed by partisan governors and they rule on laws passed by partisan lawmakers.

While voters may base their evaluation on political issues, the commission is not supposed to take any of that into account. Instead, the commission relies on a series of surveys from attorneys, jurors, witnesses and other people who directly observe judges’ performances in the legal system to gauge how a judge is doing.

Besides those surveys, the commissioners weigh comments from calls to the public at their meetings, judges’ disciplinary records and calendars, past survey results, and if things are precarious enough to call a judge in, what they have to say for themselves.

“We're the only entity out there that has the mandate and the ability to really gather the unvarnished views of the people who are encountering the judge on a regular basis. That's really the crux of what it is that we try to accomplish and relay to the public,” said Commission Chair Auther, an attorney who’s been on the commission since 2012.

All that voters can see in the reports are data sets of survey results.

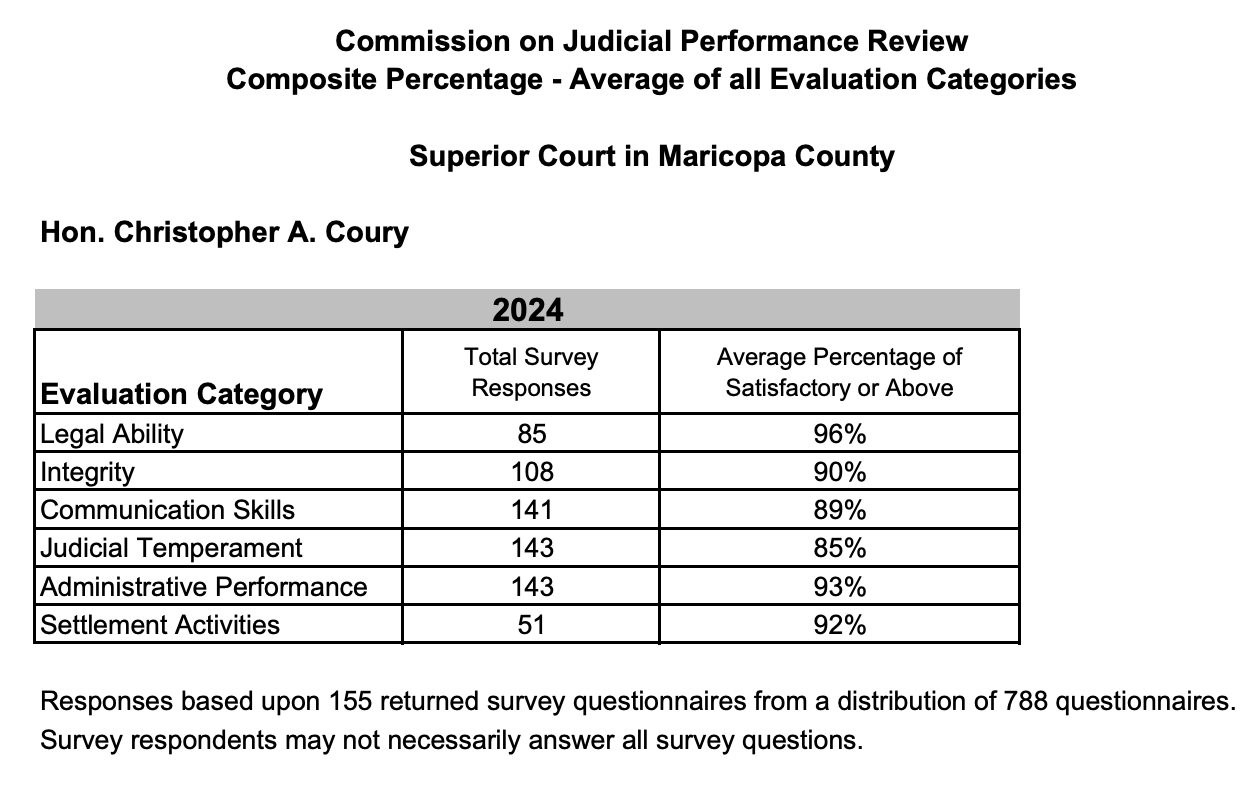

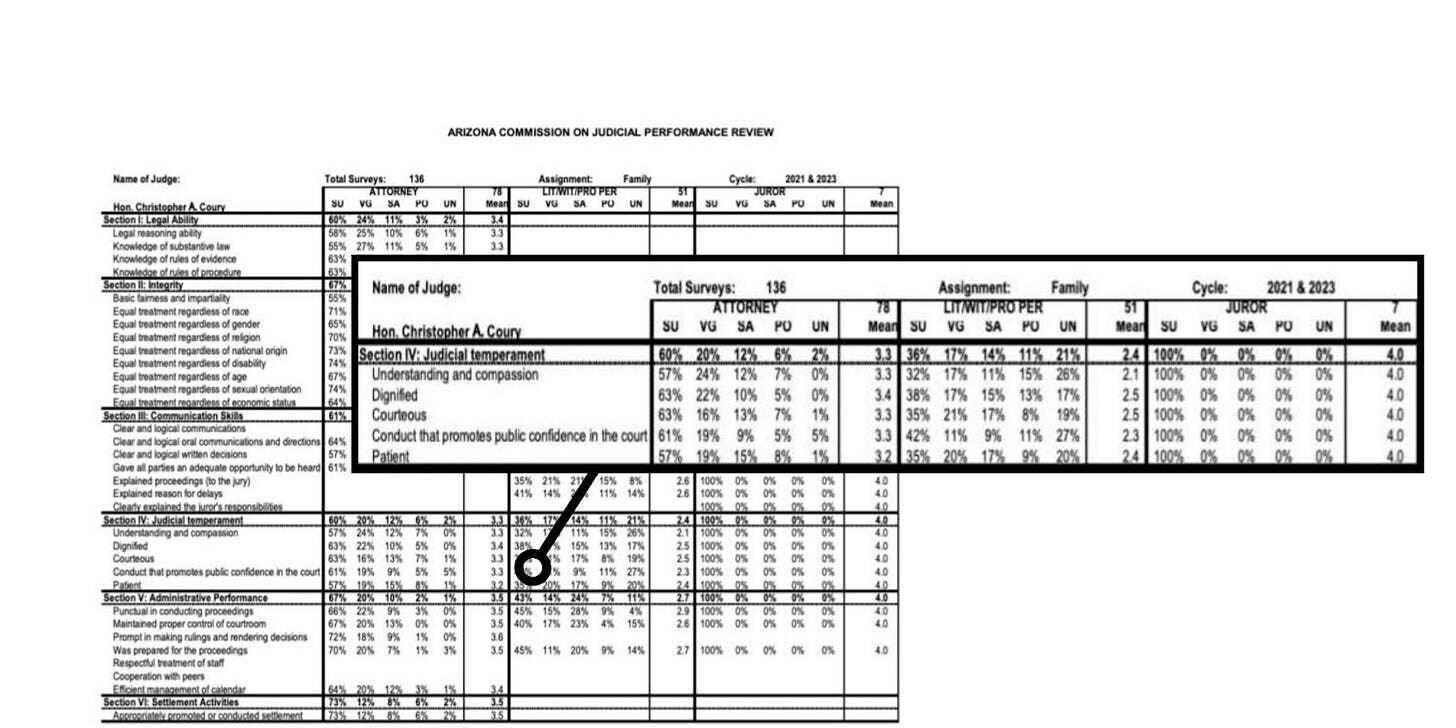

The first page of Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Christopher Coury’s report, for example, has an 85% score for his judicial temperament. That’s based on the average number of people who gave him a “satisfactory” rating or above.

Looking any deeper into the reports is not only an assault on the eyes — it’s difficult for the average voter to understand, beyond the summary the commission puts in a box on the first page of the reports.

But if you drill down to see how Coury got that 85% grade for temperament, it gets even more confusing.

Respondents have five options when rating a judge: unacceptable, poor, satisfactory, very good or superior.

On the third page of his report, the numbers show that 8% of attorneys and 32% of litigants, witnesses and people representing themselves rated his temperament as poor or unacceptable.

And those percentages are based on varying amounts of surveys submitted for each judge. Out of more than 30,000 questionnaires sent out for review of the 42 Maricopa County Superior Court judges, only 20% of them were returned — ranging from 56 to 248 surveys to score each judge.

It’s not a valid statistical analysis, and the commission recognizes that.

“We're not assigning grades here. We're not assigning percentages. We're asking people who had contact with the judge to give us their unvarnished views about the judge's performance of these categories,” Auther said.

Still, the reports are the only source most voters have.

A lot of the time, voters just vote “yes” for all the judges on their ballots, Klumpp found in his research.

As of 2020, he found Arizona voters supported judges at a higher rate than voters in most other states that hold retention elections.

There are exceptions, however. He’s seen ideological voting against specific judges, and what he calls the “Arpaio effect.” Joe Arpaio’s controversial tenure as Maricopa County Sheriff correlated with a reduction in Maricopa County judges’ retention approval rates.

The national news of Arizona’s now rescinded abortion ban, which unlike Arpaio, directly ties to the judiciary, could certainly bring another wave of “no” votes.

Still, Klumpp thinks having a retention commission that publishes surveys on judges can be effective in helping voters make decisions about retaining them truly based on merit, as the system was meant to accomplish.

However, that’s if the reports voters see are “simple enough for them to understand and apply.”

“There are places where they deluge the voters with all kinds of ratings and all kinds of numbers that voters are never going to take the time to sit down and sort through,” he said.

It’s unlikely most of Arizona’s voters will study the barrage of numbers on the commission’s reports. But there are other options.

Cathy Sigmon started publishing a “Gavel Watch Report Card” in 2020 after finding the information in the commission reports was “simply insufficient.”

It took three volunteers six months to complete this year’s report, which is published by Civic Engagement Beyond Voting, or CEBV, a nonpartisan (but progressive) nonprofit that advocates for citizens to participate in local government.

The report gives voters “Yes,” “Yes with reservations” or “No” recommendations on whether a judge should be retained. And it explains why.

The methodology includes commission reports, public websites where people can report their experiences with judges, financial statements, social media and other important context.

“We are looking for judges that bring covert bias onto the bench,” Sigmon said.

For example, CEBV recommended voters not retain Court of Appeals Judge Angela Paton, citing her ties to the Federalist Society, a conservative and libertarian legal organization that’s been extremely consequential in getting right-leaning judges appointed. And her husband is Jonathan Paton, a former lawmaker who now serves on the Appellate Court Judicial Nominating Commission and fought to legally validate Proposition 137, the judicial retention-diminishing ballot measure.

Yet, the commission gave Paton nearly flawless scores and recommended voters retain her.