Homeownership has become a pipe dream for many Arizonans.

Hundreds of thousands of people can’t afford a home, but only a few key players control housing reform at the state Capitol: those who build houses, and the entities that regulate how they’re built.

For the past two years, the biggest battle over housing has been over a policy to force cities to let developers build smaller homes.

The Arizona Starter Homes Act, now in its second year of stakeholder negotiation, would prohibit cities and towns from regulating the kinds of design features new homes have, the building materials used to make homes, size of homes and the lot size they’re built on.

The basic idea is that limiting zoning and aesthetic requirements would make homes cheaper to build and cheaper to buy.

Opponents, like the League of Arizona Cities and Towns, which represents the state’s municipalities, argue that reduced building costs won’t necessarily get passed down to consumers.

But developers who have to fight with cities’ zoning restrictions say they’re more than willing to build smaller, cheaper housing. They just can’t get past the red tape.

The housing crisis impacts all Arizonans, and the Arizona Starter Home Act could dramatically change the housing market.

It’s also one of the highest-profile bills at the Capitol. Hundreds of stakeholders have signed in against and for the House and Senate’s versions of the starter homes bill.

Gov. Katie Hobbs vetoed the same bill last year, citing opposition from cities and the Department of Defense’s concerns about higher-density zoning near military bases.

Republican Rep. Leo Biasiucci tried to address some of her concerns before reintroducing the bill this year by exempting land near military facilities from the decreased regulations.

The bill was scheduled for a vote in the full House yesterday. But got pulled from the calendar at the last minute as negotiations once again stalled out.

Hobbs isn’t committed. Her office told us they’re taking part in stakeholder discussions this year.

There are a lot of key players at the negotiating table to satisfy.

The cities

The central tension in the Arizona Starter Homes Act is between cities and the state.

A lot of housing reform at the Legislature happens by forcing municipalities to allow developments and adopt zoning codes to make it easier to build housing.

But most cities don’t like being told what to do by the state, much less lose control of what development looks like in their areas. More than 20 cities and towns have opposed the starter homes bill, which is moving as mirror bills1 through the House and Senate.

Backers of the bill blame burdensome, city-level zoning restrictions for limiting the housing supply. Developers have to work with a complex set of rules restricting where houses can be built and what they look like.

Last year, Arizona mayors held a press conference urging Hobbs to veto starter homes. They argued it won’t result in affordability and limits cities’ abilities to address the crisis themselves. Buckeye Mayor Eric Orsborn testified this year that one of the country’s fastest-growing areas is already working on building single-family homes.

The League

The League of Arizona Cities and Towns represents municipalities’ interests at the Capitol, and they’ve successfully opposed state preemption bills in the past, like one that would require cities to allow “by-right” housing that fast-tracks affordable units near transit lines.

Tamer versions of some housing bills passed last year with the League’s consent. But the League stood firm on its opposition to the starter homes bill.

Each lawmaker represents a subset of cities and towns they have to answer to, and the League serves as a powerful unifying voice for localities.

And state preemption bills don’t go through the Capitol without the League’s input.

This year, lobbyist Nick Ponder is the League’s point man. He calls the starter homes bill “the build whatever you want to bill.” Ponder says zoning isn’t the issue, and municipalities should be able to make their own choices.

“For 100 years, this development structure has been a three-legged stool between municipal planners, developers and residents, and that has worked out,” Ponder said at a Senate committee hearing. “This bill just takes two legs of that stool and throws them away and says ‘developers do what you want.’”

Besides playing defense against the Starter Homes Act, the League is pushing its own housing legislation this year.But even the sponsor of the bill doesn’t fully support it.SB1698 calls for municipalities with more than 30,000 people to adopt zoning rules that allow starter homes on at least 10% of new single-family developments. Those homes have to be sold below a price that’s 120% of the area’s median household income and can only be sold to families who make less than 120% of the area’s median household income. In Phoenix, that’s about $90,000.The League argues creating a path for starter home construction would compound the housing crisis if mega corporations aren’t prevented from buying up the houses.Republican Sen. Vince Leach, who sponsored SB1698 on the League’s behalf, says he doesn’t like the price controls that his bill contains. But he volunteered to sponsor the legislation since he also doesn’t fully support the Starter Homes Act.It’s a starting point for negotiations.“I’m really caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. The only thing I knew to do is, like Theodore Roosevelt said, the man in the ring. So I jumped in the ring,” Leach said.The senator said stakeholders held a meeting Tuesday without much agreement. He’s waiting to see “where the dust settles.”

Political allies

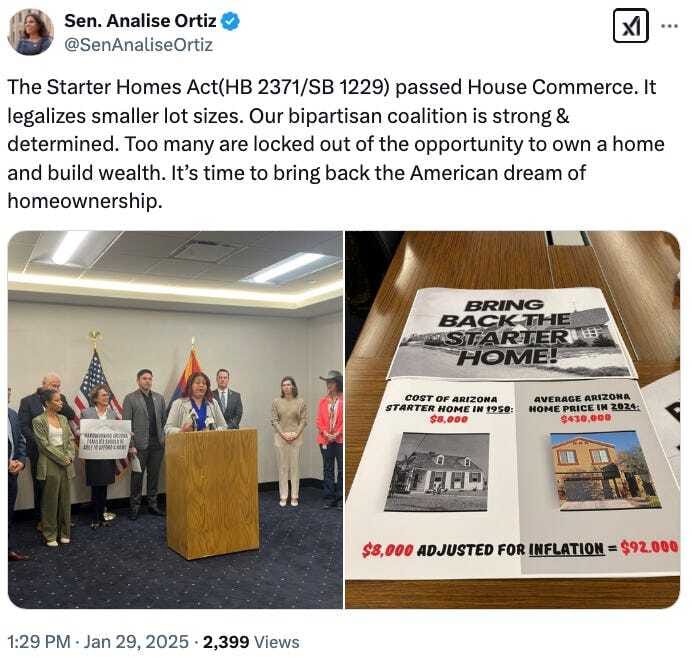

The starter homes bill has bipartisan support because of the rare common ground within it: Republicans espouse private property rights and Democrats want to compel cities to build affordable housing.

Democrat Sen. Analise Ortiz has prioritized housing reform since taking office in 2022 representing Maryvale. She has championed the starter homes bill and avidly challenged its opponents — she asked several testifiers who spoke against the bill at the Senate committee how old they were when they bought their first home and for how much.2

“I am 31 years old, and I cannot afford to own a home in the state where I currently govern, in the state where I was born and raised, and so many of my constituents are in this same situation,” she said.

Republicans are largely on board in the name of deregulation. They introduced this year’s legislation at a press conference where Senate President Warren Petersen, who works in new home construction, said “regulatory hurdles” are driving housing costs up.

“The American Dream has become unattainable, and government is the problem,” he said. “We have an issue of supply and demand. We need to bring prices down.”

Political opponents

But the fault lines on the Starter Homes Act don’t fall neatly along party lines.

Democratic Sen. Mitzi Epstein is concerned about corporations taking advantage of the law and said she’s “skeptical of plans that seem to be brought by builders.” Sen. Brian Fernandez shared that sentiment.

“I don't think that this bill is going to do what I'm being told it'll do,” he said. “I don't think that it is for starter homes. I think it's just a way for developers to have easier access to making a larger profit in a quicker way.”

Democratic Rep. Betty Villegas, Pima County’s former housing program manager, said it’s “premature for us to vote on a preemption bill that will hurt communities” that are already working on housing affordability.

Republicans are also divided. Last year, Rep. Matt Gress said the bill would do nothing to create starter homes, and called it a “major giveaway to developers.”

The governor

Last year’s version of the bill barely passed each chamber of the Legislature, but it earned roughly equal support from both Democrats and Republicans.

But bipartisan support means nothing without the governor’s approval.

Hobbs said in her veto letter that over 90% of people who reached out to her requested a veto, and city leaders were concerned about “impacts on infrastructure … lack of affordability guarantees, and potential legal consequences.”

Besides removing a provision allowing the smaller homes near military installations, this year’s bill is pretty much the same version she vetoed last year. It’s unclear if it will end up in a place Hobbs is willing to sign into law.

Hobbs’ spokesperson, Christian Slater, said the governor’s team is working on setting up a stakeholder meeting next week.

The builders

Opponents argue that giving builders smaller lot sizes to build houses on doesn’t mean they’ll sell them for less.

While there are many developers creating housing throughout the state, Spencer Kamps, the vice president of legislative affairs for the Home Builders Association of Central Arizona, is one of the main development lobbyists at the Legislature.

He said smaller starter homes are in high demand. Builders want to make homes, but municipal zoning boards aren’t letting them.

If given the chance, Kamps said builders would offer smaller, lower-cost homes.

“We would do it as quickly as possible. The fact of the matter is that every builder is trying to get into the entry-level market because of high-interest costs and consumer demand — there's a lot of people that want that product,” he said. “In the Phoenix building market, we're simply selling more units on the lower price spectrum than we are on the higher.”

Who else cares?

Cities and developers seem to be dominating ongoing discussions and committee hearings on starter homes. But housing affects everyone.

Groups like Chispa Arizona, a progressive climate advocacy group, and the Goldwater Institute, a conservative think tank, have supported the Starter Homes Act — for very different reasons.

But at the end of the day, this is a fight between cities and developers, Leach said. Lawmakers can help guide the discussion, and the governor will give it the ultimate thumbs up or down.

“It’s a decision between the builders and, actually, the cities and towns, of which way they want to go and, if they're going to negotiate, which bill is easier to negotiate on?” Leach said.