Is ChatGPT running for office?

These candidates are getting a little too intelligent if you ask us.

Last week, we got a tip that we had been waiting for1 — a Democratic congressional candidate had allegedly been writing their policy statements, campaign emails and even opinion pieces submitted to newspapers with ChatGPT.

It’s one of those moments you just knew would happen eventually — AI language models like ChatGPT are forcing all sectors of society to reexamine the line between being efficient and being lazy, between using the tools at hand and cheating, between human gobbledygook writing and artificially intelligent gobbledygook writing.

Why should politics be any different?

So we started investigating. Sure enough, a whole lot of content from the candidate in question consistently hits above 70% likely to be written by artificial intelligence by AI detectors like GPTZero, QuillBot and Sapling.

Which got us thinking, if this candidate is using ChatGPT to write their content, what are the odds that they’re the only one?

And after thorough research, we can conclusively tell you that many Arizona political candidates are using ChatGPT to write or enhance at least some portion of their campaign materials.

That is, at least, if you believe the AI detectors.

Conor O'Callaghan, a Democrat and first-time candidate running in the crowded primary to take on Republican David Schweikert in Congressional District 1, is incredibly verbose about his various policy positions.

“With a deep understanding and appreciation of the pivotal role that women of all ethnicities, sexual orientations, and socio-economic backgrounds have played in shaping the fabric of the nation, and an acute recognition of the persisting wage disparities that continue to persist – especially in minority communities – the O'Callaghan campaign stands resolute in its dedication to fostering a more equitable future,” his three-point plan to address gender inequity begins.

“This commitment finds expression in the unveiling of a comprehensive three-point equity plan, a transformative, fiscally responsible blueprint designed to bridge the gender pay gap that persists within the American workforce. Rooted in personal connections and driven by a deep-seated commitment to fairness and justice, this multifaceted plan addresses critical dimensions of economic security, transparency, and family support,” it continues, for another four dense pages.

GPTZero, one of the leading artificial intelligence language detection tools, gives O'Callaghan’s plan a 97% chance of being AI-written. Sapling, another popular AI detection tool, calls it 99.9% likely AI. QuillBot, a third tool, calls it 100%.

Another dozen or so documents that O'Callaghan has produced consistently score above 60% likely AI written across the three detection programs.

That seems pretty dead to rights.

But the O'Callaghan campaign vehemently denies it used an AI writing tool to crank out the prolific new candidate’s policy positions.

Campaign consultant Matt Grodsky offered up a variety of explanations for the “false positives” that kind of make sense: They used Grammarly to help edit. They’re boring political documents that just inherently read like AI. The campaign wrote a lot of documents and turbocharged them with buzzwords for search engine optimization.

And while that dense block of text sure reads like a robot wrote it, there’s one big reason to give O'Callaghan the benefit of the doubt.

According to most researchers and even the company behind ChatGPT, AI writing detection software is pretty much a sham.

Rijul Gupta is the CEO of Deep Media, an AI detection company that has contracts with the U.S. military and major companies. After seeing our Kari Lake deepfake, he reached out to note that his software had no problem detecting it as fake.2

But unlike video and audio, AI-generated or enhanced text is “insanely hard to detect,” he warns, because text doesn’t offer nearly as much data to analyze.

“If you look at a paragraph of text, it has 200 words in it, right? That's 200 data points that you can pick out. And that's it,” he explained. “Audio has 16,000 pieces of data every single second. A video has … 25,000 pixels, which are pieces of information, every frame. And that's 30 frames per second.”

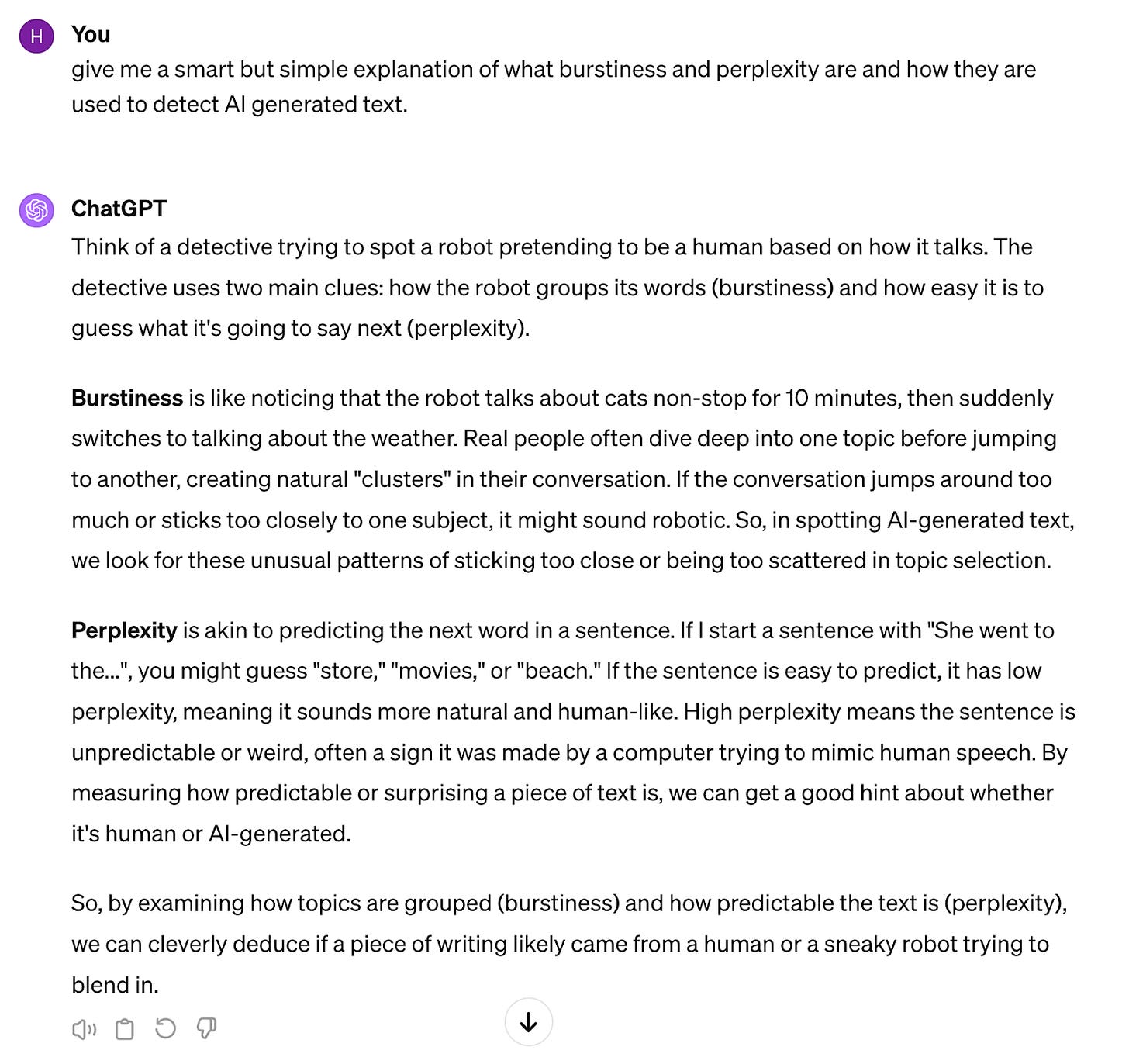

AI text detectors use two main factors to determine if a human or a robot wrote a block of text, he explained. They’re called perplexity and burstiness.

High burstiness means thoughts follow each other logically, like human thoughts do. Low burstiness is like extreme ADHD, or ChatGPT. Perplexity is essentially how predictably each sentence ends. Is the next word what you’d expect a human to say?

Here, our intern can probably explain it better.

But burstiness and perplexity are not foolproof AI fingerprints. For one thing, text is very easy to edit. With a few tweaks, a piece of writing can go from 100% likely to be AI-generated, to 0% likely. The reverse is also true — AI internet researchers have shown that a few clunky words in a paragraph can trip up the detectors and generate false positive results.

OpenAI, the parent company of ChatGPT, pulled its AI detector off the market after just a few months, saying it wasn’t reliable and provided false positive hits, including on pieces of Shakespeare's Macbeth, the Bible and the U.S. Constitution.

That’s in part because ChatGPT and other language AI models were trained on those documents and learned to write kind of like them. So, ChatGPT writes like a cross between Shakespeare and boring political documents, and AI detectors think both are robots.

Still, if you know what ChatGPT writing looks like, you probably recognize the tone of some of O'Callaghan’s policy positions and emails. If not, it just looks like the usual political gobbledygook.

And therein lies the problem, according to the O'Callaghan campaign: Political policy papers and op-eds inherently read a lot like ChatGPT.

They’re verbose, boring documents that by design rehash old ideas, like Medicaid, tax policy or gender equality.

“On a lot of this stuff, we went very heavy on passive jargon, and heavy (SEO) tags to fill up content and increase SEO, because he was the last candidate in the race,” and that helps him rank on Google, Grodsky said. “And so we put all that stuff up there to help with his site, but I can vehemently say we did not use AI for it.”

We asked our art intern, ChatGPT, to draft up a four-page, three-point plan to address gender inequality, from the perspective of a Democratic congressional candidate.

Check out our ChatGPT version compared to O’Callaghan’s version. They got the exact same score on GPTZero!

While some companies proudly do use AI tools like ChatGPT, Grodsky’s firm strictly does not. It has a policy against employees using ChatGPT for anything that’s published, exactly because he’s afraid it would reflect on a candidate in accusations like this, which there’s no real way for them to disprove, even if it’s false, he notes.

We weren’t the first reporter to come pounding on Grodsky’s door, he said, and after he first heard the accusation, he ran content from all the other candidates in CD1 through AI text detectors. Most of them show up with at least some degree of AI content, “which I don't think necessarily means they used it,” Grodsky said.

We’ve run a lot of content through several different AI detectors in the last week. If we run enough of their content through, almost anyone gets a few hits suggesting some AI generation or enhancement.

And detectors can absolutely deliver false positives. A section in one of Schweikert’s newsletters,3 for example, shows up as 85% likely to be AI-written in Sapling, and 0% in GPTZero.

But no candidate we found came back with nearly as many hits, at as high a rate of confidence, as O'Callaghan.

While a few false results are to be expected, a clear trendline like that is rarely wrong, Gupta said.

“From an expert opinion, I think it's highly likely it was AI generated,” Gupta told us. “To me, it would be really stupid if it wasn't AI-generated. If they're writing content for SEO purposes, AI is going to be so much better than any human being at doing that. So if they didn't use AI, I would think less of them just as marketers.”

All across America, from courtrooms to cubicles to crockpot cookbooks, people are passing off ChatGPT’s writing as their own.

So much so that we’re experiencing a fundamental shift in what is considered acceptable levels of “help” writing. Some students are being taught to use ChatGPT responsibly, to assist in research and perhaps help outline and develop thoughts, rather than asking it to write a 5,000-word book report. Others are banned from using ChatGPT altogether.

As the Washington Post detailed last year, many are being falsely accused of having ChatGPT write for them and being punished for suspected cheating, even though there’s no clear way to prove whether a human or an AI model wrote something.

And maybe that’s not even the right question.

While staunchly maintaining his candidate and team did not use AI to write for them, Grodsky argues that maybe candidates should — or at least it’s worth a conversation about where we as a society want to draw the line. The American Association of Political Consultants voted unanimously to condemn AI deepfakes, Grodsky noted, but how the industry deals with text generation is still far less clear.

“If you're prompting AI to write something, and it's vetted and approved by the candidate and the team, how is that different than a copywriter or a speech writer writing it for the candidate? As long as it's not lifted from anything and as long as it's not plagiarism, what is the line?” he asks.

We as a society haven’t really decided that yet.

The act of writing isn’t just generating text. It can offer a window into the mind of the writer and how they think. How rational they are. Where they’re coming from and how they work through problems. And often that’s all voters have to go on.

Then again, it’s easy to be outraged that ChatGPT would write a candidate’s positions. But would anyone be outraged to learn that a staffer wrote them?

What would the average voter want their candidate to do? Utilize the tools at hand to focus on more important things? Or to pour their real heart and soul into op-eds that truly reflect their thinking?

Most voters probably haven’t actually thought it through.

For Gupta, the AI expert who spots deepfakes for the U.S. military, it’s a no-brainer.

“My opinion is that it's like a calculator. If my accountant came to me and said, hey, I just did all your taxes. You're good to go. I didn't even use a calculator. I wouldn't pay that accountant. Like, use a calculator!” he said.

As Arizona’s foremost publication covering the intersection of politics and artificial intelligence, apparently.

Gupta also taught us a new trick to spot AI audio deepfakes — vocal fry at the end of a sentence, especially when it ends in a vowel.

We ran a half-dozen editions of the Agenda through but couldn’t find any that clocked in at more than 1% chance it was AI-written. We’re very bursty writers!

A.I. or staffer, does it matter? Candidates have to attend events, meet their potential constituents and fundraise (for hours and hours and hours). Surely, voters knew that many (or most) candidates and elected officials have staff that write their content. I can’t count the number of published OpEds I have written for others and no one will know who/want/when/where. You don’t write and tell unless you write for the big leagues (state of the union, state of the state). Policy platforms, priorities, website content, the simple invite to the coffee with the candidate…that is what strategists and staffers were paid to do. The candidate makes the decision where they want the ship to sail, but it’s the paid staff and volunteers that that are performing the below deck grunt work. The candidate needs to spend a majority of their time interacting with voters- not stuck at their laptop prevaricating on word choice. And, political speech often sounds stilted. Trust me, there aren’t that many creative ways to write about property values and taxation without repetition. Hence, the tortured phrases that sound unnatural: home investment and excise, real estate and tariff, housing toll, etc. (In my defense, I’ve never written “housing toll” in place of “property taxes” - that’s just the example that came to the top of my head while using thumbs to comment on my tiny phone.) If one has the opportunity to be brief and concise- no problem. But, when you have to explain in more detail, it’s difficult to find “natural feeling” synonyms so you aren’t left using “women’s reproductive health” or “public education” or “border policy” 50 times in one piece.

You know who writes almost all their own content and do so better than anyone else? Teachers that run for public office.

I mean really if we did elect an A.I. to office could it be any worse than what we have now? I'd be in favor of David Schweikert using A.I. at least there would be some intelligence.