With the ballot mostly set, it’s time to run a background check of the candidates that will be on your July ballot.

For us reporters, dirt-digging season is one of the best seasons of the two-year election cycle. We get to comb through politicians’ personal, political and sometimes criminal history.1

We’ll get to those important policy questions soon, but first, we have to learn who these people wanting to represent us really are.

This year, we thought we’d bring you along for the fun. So we’re showing you our trade secrets by providing a run-down on how to do a quick (semi) comprehensive background check of a candidate running for office.

Legal history

The first stop is the courthouse. Or more accurately, courthouses.

There are a lot of ways to dig through someone’s legal background through criminal and civil court cases. Unfortunately, that means you have to search a lot of ways if you want a comprehensive view of a candidate’s potential legal history.

If you want to know if they’ve ever been accused or convicted of a crime, first you gotta know what type of crime you’re looking for.

Was it a federal crime? A state crime? Here in Arizona or another state? Or are we talking about a petty crime that went through a city court? If so, which city?

It gets complicated very quickly, even if you know what you’re looking for.

Luckily, the Arizona Supreme Court website provides a simple search for most Arizona courts. It’s the best tool to scrape the widest set of sources in the shortest amount of time, but it’s not perfect.2

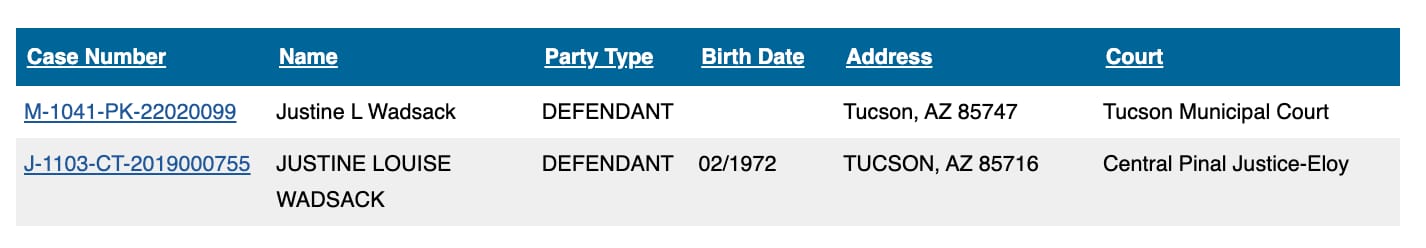

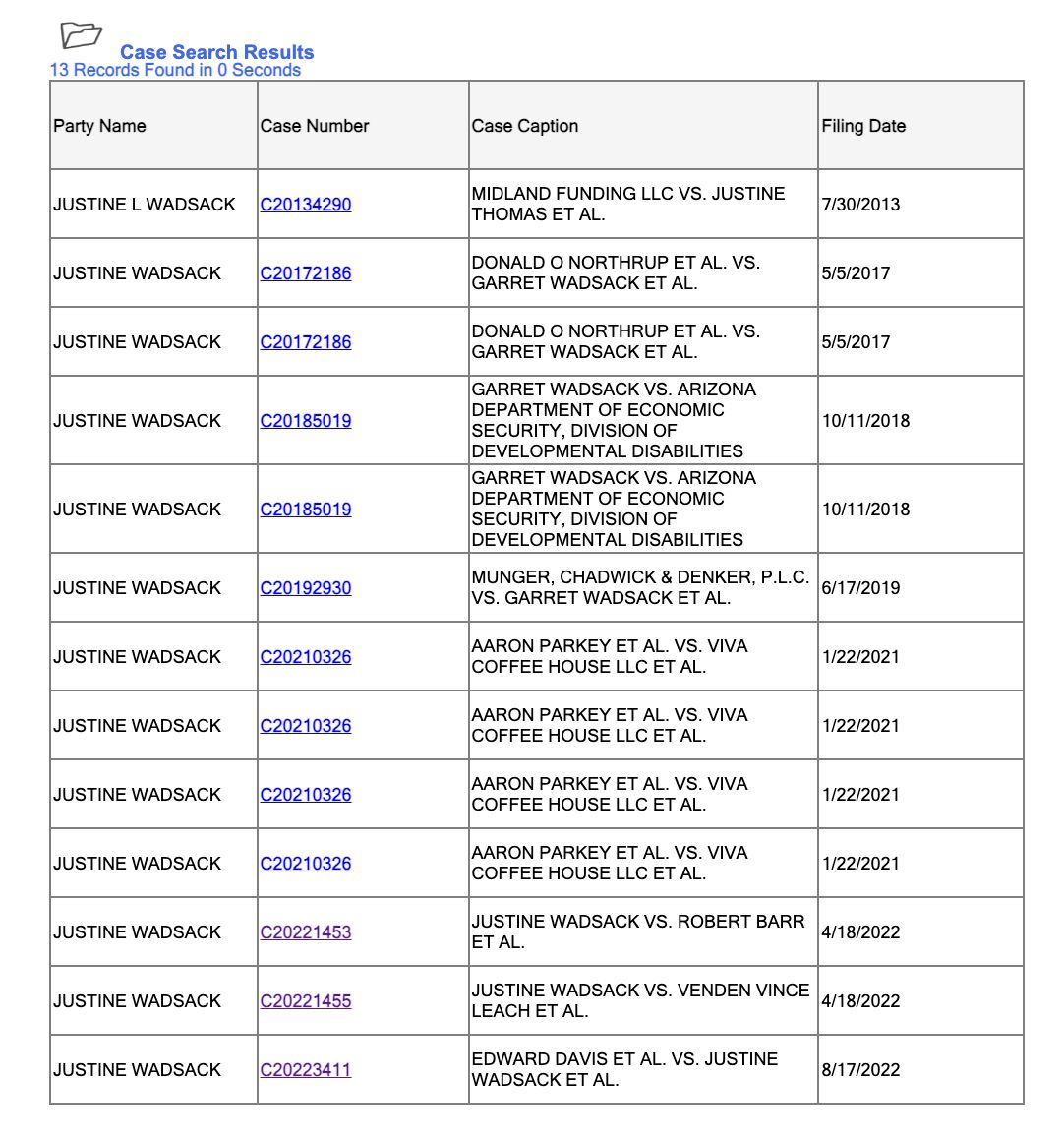

For example, searching for Republican Sen. Justine Wadsack pulls up a few petty infractions with the law – an expired registration case in Tucson Municipal Court, and a speeding ticket from Pinal County. You’d walk away from that search thinking “no big deal.”

But the Supreme Court search doesn’t include Pima County Superior Court. If you know to look there too, you’d probably come away thinking her legal life is much more complicated.

But if you want to dive into the documents, you’ll probably have to go to yet another website.

Criminal and civil cases are tried in each county’s superior court. You can get an account on eAccess to see Arizona superior court records for most cases filed on or after July 1, 2010. That will cover most of the big stuff.

Municipal and justice courts are where misdemeanor crimes and petty offenses are handled. You can find out if the local court has documents online. But you can always go to these courts in person. Most of them have computer terminals where the public can search through and read court documents for free.

Of course, that’s just Arizona courts — and only the stuff that actually makes it to court.

Campaign finance

Candidates must report who’s giving them money to campaign and how they’re spending that money.

Statewide and legislative candidates and their campaign committees have to file these with the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office, which has a searchable database here.

Federal candidates file with the Federal Elections Commission.

And local candidates file with either their city or county. The laws and regulations are different at each level and all the forms are in different formats. It’s a mess.

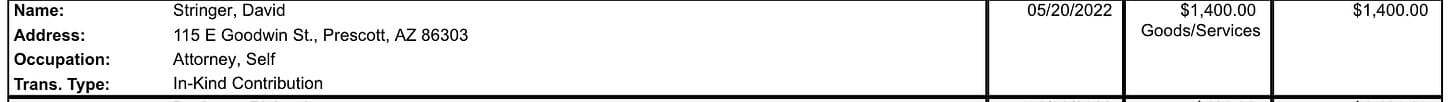

But if you can find and navigate them, the forms are treasure mines allowing you to see who supports candidates and how they choose to spend their resources.

That’s how we know former state Rep. David Stringer, who was convicted of sex crimes against children, contributed to Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne’s campaign in 2022. The ordeal caused Horne to cut ties and refund Stringer’s contributions — eventually.

Financial Disclosure Statements

Candidates are also required to tell us how they make money and other financial details.

Unfortunately, the forms mostly aren’t available online. Like campaign finance, there’s no central repository for the documents, so you have to check your city for city candidates and county for county candidates.

The Secretary of State’s Office only posts financial disclosure statements from those who are already elected. To get the statements for candidates, you’d have to file a public records request.

We previously broke down the 2023 tranche of lawmakers' financial disclosure records and found some interesting tidbits, like that Republican Sen. David Gowan received a bunch of gifts from powerful lobbying groups, that Democratic Rep. Mariana Sandoval went to the Super Bowl and a Gwen Stefani concert on Arizona Cardinals owner Michael Bidwill’s dime and that Sen. Anthony Kern owns a private investigation service.

The financial disclosures are key to revealing conflicts of interest, like that Gowan sells fireworks and has spent the last decade slowly expanding Arizona’s list of legally permissible fireworks. Rep. Kevin Payne owns K Star BBQ food trucks and has sponsored several bills over the years benefitting the food truck industry.

Curious about the companies that candidates own or nonprofit boards they serve on? Head over to the Arizona Corporation Commission search, where you can see who they’re in business with.

We love providing simple guides to political processes to the public, so today’s edition is available to everyone. But we depend on subscriptions to keep this operation going, so a subscription in lieu of fireworks and food truck sales would be great.

Residency

State lawmakers and usually local officeholders — like members of the city council or board of supervisors — are required to live in the districts where they run for office. But sometimes their home district isn’t politically convenient.

Take the case of former Rep. Darin Mitchell, who got to stay on the ballot in 2012 even though a judge ruled he doesn’t live there. A neighbor ratted Mitchell out to the media after seeing he claimed to live on her street in Litchfield Park in a vacant house she recognized.

But how can you verify someone’s residency if you don’t have the neighborhood watch on your side? Property records are a good start.

Some county assessors’ offices have online databases of property records that show you who owns a property. That only works for actual homeowners, though, and not renters.

Last year, then-Capitol Times Reporter Camryn Sanchez found property records showing Sen. Wendy Rogers and her husband bought a property in Chandler and signed records attesting she lives in Tempe. That’s more than a rock’s throw away from the Flagstaff district she represents.3

County recorders' offices also have deeds, liens and other public documents that can tell you about what property a person owns and where they live. You can request these records, or search for them online if the recorder has the option. The Maricopa County Recorder’s Office has a recorded document search.

Social media presence

Checking out a politician’s social media presence is pretty basic. But oftentimes, a good scour can tell you all you need to know.

Social media content has driven some of our favorite recent stories.

Take Green Party candidate Mike Norton’s LinkedIn bio, for example, which says he works with companies that transport arms, ammunition, explosives and radioactive materials despite running for a party that espouses demilitarization.

LD24 Democratic House candidate Mario Garcia’s Facebook page showed lots of love for far-right Senate hopeful Kari Lake.

LD1 Republican Senate candidate Mark Finchem, who campaigned to become Arizona’s top election official, posted a picture of his ballot at a polling place on Twitter. It’s illegal to take a picture of your ballot at a polling place. He claimed he “wasn’t aware” it was illegal, despite voting for the law.

Voting history

You’d like to think those asking for your vote would have bothered to vote before. That’s not always the case.

Back in 2010, Hank found that House Republican candidate Terri Proud, who was running in a contested primary, had never bothered to vote in a primary election before.

You can check out someone’s voting history (that is, if they’ve voted, not how they voted) by requesting their records from the county recorder’s office where they live. You can also go to most recorders’ offices to take a look in person at computer terminals.

It’s also important to check if a candidate is registered with the party they’re running for. And for how long they’ve been a member of the party.

Democratic voters in the Phoenix-based Congressional District 1 may like the fact that two of their six primary candidates — doctor and former Democratic state Rep. Amish Shah and Marlene Galan Woods, the widow of former Republican Attorney General Grant Woods — are former Republicans, considering they’re running to challenge Republican David Schweikert in a competitive district. Or Democratic primary voters may want a true blue Democrat representing them.

But either way, it’s good to know.

Signatures

The first thing a candidate must do to qualify for the ballot is be nominated by their would-be constituents who sign “nomination petitions.” And one of the simplest ways to judge a candidate’s character is to check if those signatures are even real.

But when someone submits the number of signatures they need to qualify, election officials don’t check if they’re valid. It’s up to opponents, reporters and citizens to scope out the signatures and make sure the signees are registered voters, live in the appropriate district and actually exist.

This process recently led Rep. Austin Smith to drop his reelection campaign. A citizen accused him of forging 90 signatures, and Smith didn’t want to fight the allegations in court. Several of the signatures in question had a “striking resemblance” to Smith’s, according to the legal complaint.

Besides how the signatures look, you can check a signer’s voting registration at the recorder’s office to see if they’re a qualified elector of the candidate in question. The voter must live in the same district as the candidate who they signed a petition for and belong to the same party as them (except for independent candidates).

That means going back to the recorder’s office, to look up each individual voter.

However, legal challenges to candidates’ petitions must happen within two weeks of the close of the filing date. So you won’t have the chance to pop another alleged cheater like Smith for another two years.