Arizona politics and policy are complicated, so we love to provide you cheatsheets to navigate the bureaucratic maze.

Over the years, we’ve brought you guides on how a bill becomes a law, how to find key information on government websites, how to get public records and even how to expunge your criminal record for weed.

This month, as lawmakers return to the Capitol, we’re delivering the lowdown on the Legislature.

Today — We break down how the annual budget gets built. Sound boring? IT’S BILLIONS OF DOLLARS OF YOUR MONEY!

Next Friday — We’ll delve into the biggest issues, and solutions, dominating the legislative session. Most of this year’s bills will start trickling through the process by then, so we’ll have a much better idea of what ideas have juice, and which bills will end up in the trash.

And ICYMI — check out last week’s digestible directory on who’s who at the Capitol.

If you like this kind of explanatory journalism, we’ve got good news for you! There’s an easy way you can help create more of it!

Gov. Katie Hobbs will unveil her executive budget proposal today, triggering the starter’s gun in the annual budget battles.

While legislators file somewhere around 1,500 bills a year, their most important duty is to pass a balanced state budget. It’s really the main event of what lawmakers do in a given year. But unlike passing bills, the process of crafting a budget mostly happens behind the scenes.

This year, lawmakers have to fill an estimated $420 million hole in the current budget that ends on June 30. That means they’re cutting the bipartisan budget they wrote last year.

They’re also facing a projected $450 million deficit for the next fiscal year budget. That’s state spending starting July 1 — the budget they’re supposed to be fighting over this year.1

In essence, the state is now expected to spend or not receive almost $1 billion more than the last time policymakers hashed out the spending plan. They’ve got to make that up by cutting spending or finding more money.

That’ll take a lot of negotiating and compromise among divided branches of government.

In other words, don’t expect them to pass a budget anytime soon.

THE TEAMS

In the budget game, there are essentially two teams: the Legislature and the Governor’s Office. (The Legislature is just a very divided team.) Besides the politicians involved, each team has its own group of experts who actually understand this stuff.

The Joint Legislative Budget Committee

The JLBC advises the Legislature, and it’s staffed by economic intellectuals who create a “baseline budget” as a starting point. JLBC staff consults with the Finance Advisory Committee, a 14-member committee of public and private sector economists, along with two economic data models from the University of Arizona to put together revenue estimates for the current and next fiscal year. The JLBC crafts spending estimates based on any spending increases passed in prior years and predetermined formulas that calculate spending for things like K-12 education, which changes with growth in the student population.

The Governor's Office of Strategic Planning & Budgeting

The governor has her own staff who create their own revenue projections and write up her fiscal priorities for the state. Like at the JLBC, it starts with a baseline estimate. But this budget also includes how much money the executive branch wants to put toward specific policies.

When you hear about the “governor’s budget,” we’re really talking about her budget proposal. Legislative Republicans will have one too, as will Democrats. Each of the four legislative caucuses might even craft its own budget proposal.

But it’s only a budget when it has support from 16 senators, 31 representatives and the governor.

THE SIZE OF THE PIE

Before lawmakers can figure out how they want to spend taxpayers’ money, they have to decide how much of it they’ll have to spend.

The politicians and economists projecting the state’s revenues offer different, constantly evolving opinions on the economy. Lawmakers can choose to budget based on revenues that are higher or lower than the economists’ projections.

As a rule of thumb, the governor’s office usually puts out rosier projections than the prescribed formulas of the JLBC. Through negotiations, both entities will eventually settle on an agreed-upon estimate of how much money Arizona will have.

But it’s important to note that even if the Capitol’s main players agree on how much revenue they expect in the coming year, they can always fudge that a little to cram everyone’s priorities into the budget pie.

“You might decide to sort of loosen the belt a notch or two at the end,” as Sen. J.D. Mesnard put it.

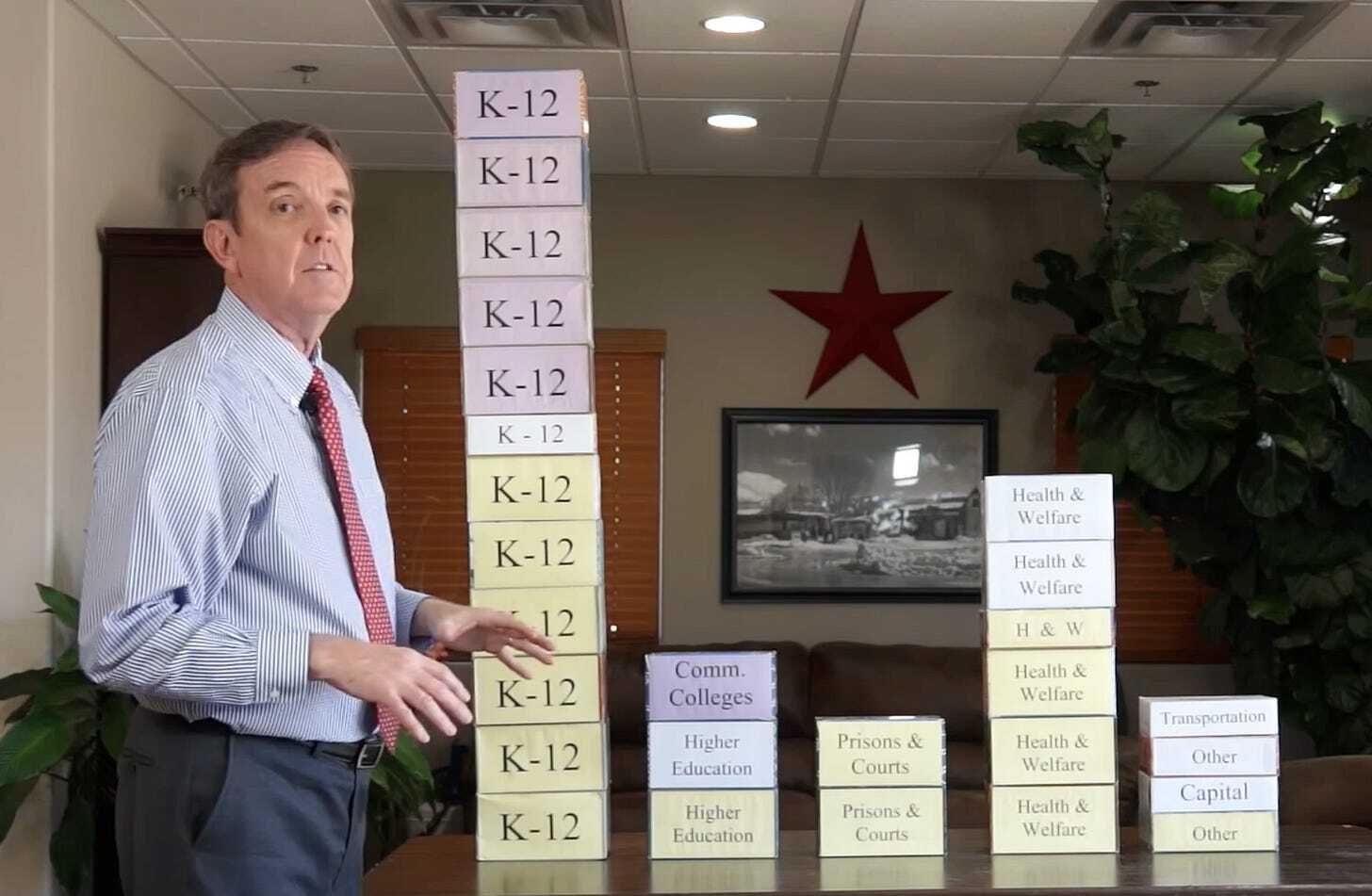

Formula spending

The state budget pays for required government programs like the state Medicaid agency, prisons and public schools. These are calculated through prescribed formulas, i.e. how many people are enrolled in AHCCCS, how many people are in prison and how many students are in school. There’s still some room for guestimation, but at the end of the day, the state has to pay for these things.

Discretionary spending

Beyond the myriad of state functions that the government has to appropriate money for each year, lawmakers throw in their own projects. All the road projects, rodeo facelifts, teacher raises and anything else above the baseline is discretionary spending.

When people talk about “the budget” they’re mostly talking about this pot of money — discretionary spending from the General Fund.2

THE PROCESS

At its core, the state budget is a political document. It’s mostly orchestrated by the Republican majority in the House and Senate and the Democratic governor.

After Hobbs unveils her budget proposal today, legislative Republicans will ensure the proposal is thoroughly scoured for the ideas they hate most to use as talking points against her.

Then her proposal is “physically used as a doorstop in the speaker's office or the president's office and never opened again by Republican legislators,” as Republican consultant Stan Barnes puts it.

Republican leaders will then release their own budget proposal as a rebuttal. That could come in many forms: a press release, their own set of spreadsheets, a social media video. But it probably won’t be actual budget bills.3

Those come much later.

The next big step in the budget battles comes on Tuesday when lawmakers on the House and Senate appropriations committees will hear presentations from the JLBC and governor’s budget office about the baseline budget and the executive budget marked with Hobbs’ priorities.

After that, there is usually a long lull in the budget action. Everyone is waiting for the more accurate, timely projections that JLBC comes up with in April, which could show revenues are higher or lower than expected.

By that time, leaders should be holding a series of three-way meetings between the governor, Senate President Warren Peterson and House Speaker Ben Toma in the proverbial “cage” where the three leaders fight it out to come to some sort of final product that all parties can settle for.4

Once the governor, speaker and president have a deal, House and Senate leaders still have to round up enough votes to actually pass that budget agreement.

It’s at this point that “budget docs” begin floating around the Capitol.

Those closely guarded spreadsheets detail the major changes lawmakers are considering in a format that lawmakers can actually read and understand.

When you see those spreadsheets, you know the budget process is getting serious.

BUDGET BILLS

Legislative leaders only introduce budget bills after they believe they have enough votes to pass the deal outlined in the budget docs.

And when they introduce those actual bills things move fast.

Those budget bills are the first chance a regular citizen has to see the budget. And usually, within three days (the fastest speed the Arizona Constitution allows lawmakers to pass bills), those budget bills are already debated, voted on and sent to the governor.

That annual package of budget bills contains two main pieces: the General Appropriations Act, or the feed bill, and the budget reconciliation bills, or BRBs.

The General Appropriations Act

This is the main bill that supplies state agencies with their operating money from the General Fund and comprises most of the budget’s allocations.

Budget reconciliation bills

BRBs cover more policy-specific areas connected to how the state spends funding buckets. BRBs changed dramatically with a 2022 Arizona Supreme Court ruling that lawmakers can’t shove unrelated policy issues into the BRBs.

Without the ability to pack all sorts of unrelated policies into the budget BRBs, “horse trading” for votes around the budget becomes all the more important. To get lawmakers to vote on the budget, the chambers’ leaders can give a lawmaker’s bill a hearing or make other concessions.

Oftentimes, just before the budget goes up for a vote, you’ll see a wave of votes on bills that had previously stalled out come back to life. Those are the horses being traded.

GOING FORWARD

The budget shortfall will loom over every budget decision this year, a stark contrast to the $2 billion surplus Arizona saw last year. And this year, lawmakers have an eye on their reelection campaigns.

We could be in for a long standoff.

Last year, Hobbs vetoed a series of budget bills Republicans passed in February that left out many items the governor’s original budget wanted. Lawmakers and the governor didn’t come to their bipartisan agreement until May, and the final product left out key Democratic priorities.

Nobody was especially thrilled with the bipartisan compromise budget, and now it’s busted.

This year’s budget negotiations could take just as long, if not longer, among a deeply divided Legislature posturing for their constituencies.

But the big difference is that in 2023, the main issue at hand was what to fund.

In 2024, the only question lawmakers will be asking is what not to fund.