A disease called profit

With less federal help, Arizonans are getting a clearer view of what “affordable” care really costs — and who profits from it.

Morning, readers!

The Affordable Care Act is about to get a lot less affordable.

As federal health insurance subsidies expire next year, insurers are hiking rates to keep profits intact.

Today, we’re unpacking the money motive that drives it all.

We can’t fix the healthcare system, but with your help, we can keep explaining why it’s broken.

Also, Tuesday is a federal holiday. We’re taking Monday off instead. We’ll be back in your inboxes on Veterans’ Day!

Fighting cancer is expensive.

Former Democratic Sen. Christine Marsh learned that firsthand after her 2021 diagnosis, even though she had healthcare through Arizona’s state employee health plan.

After losing her 2024 reelection bid and retiring from her teaching job, Marsh signed up for health insurance through the Affordable Care Act. She’s not considered in remission until five years post-diagnosis, and has to get regular testing done to make sure the cancer isn’t back.

When Marsh logged into the healthcare marketplace last weekend, she found out her monthly premiums for continued health insurance next year will jump by 170%.

Marsh isn’t sure what she’s going to do yet — she’s waiting for results from the blood tests and CT scan she got this week.

“I’m not making any decisions, because what if the cancer is back? That’s going to change every decision I might be making,” Marsh said. “I don’t know what I’ll do if it’s back.”

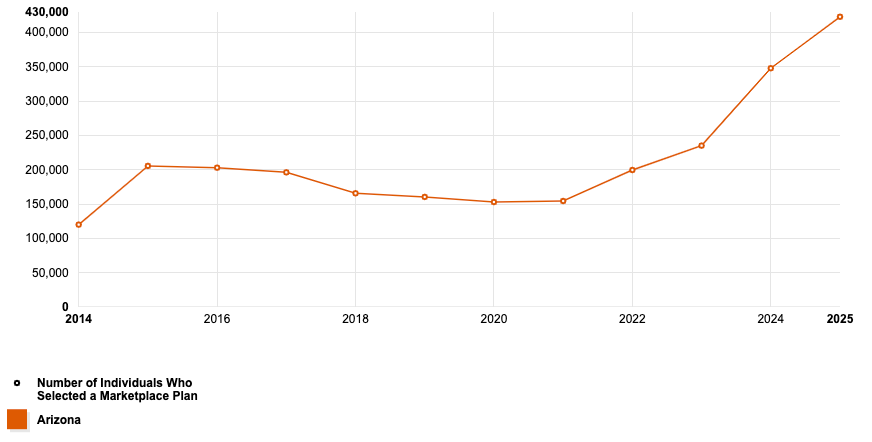

Marsh was one of several readers who responded to our callout for people feeling the sting of rising health insurance costs. She’s part of a much bigger group — more than 423,000 Arizonans get health insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace, or the ACA, or Obamacare. It’s government-regulated health insurance where recipients pay based on their income.

ACA users began logging into the Health Insurance Marketplace on Nov. 1, when open enrollment began, and finding out their monthly premiums will cost far more in 2026.

The enhanced premium subsidies that 9 in 10 Arizonans with ACA coverage rely on will expire next year. Families are now facing the full sticker price of a system that’s been quietly getting more expensive for years.

Now that federal support is no longer hiding the sticker shock, the prices indicate a larger truth of a healthcare system built to make dollars, not sense.

And more Arizonans rely on the ACA now than ever before.

While Medicaid provides coverage for those with very low incomes, the ACA picks up where Medicaid leaves off — it’s for people who aren’t quite toeing the poverty line but also can’t afford private insurance. The most a single adult without kids can make in Arizona to qualify for Medicaid is $20,815, and plenty of people still struggle to pay for healthcare while making more than that.

Private insurers sell plans on the marketplace, and the government pitches in through income-based subsidies or tax credits.

Those subsidies are currently at the center of the longest federal shutdown in U.S. history.

Former President Joe Biden juiced up the ACA’s premium tax credits under pandemic-era relief laws, and more people qualified for bigger subsidies. Enrollment hit record highs as middle-class families who were once shut out of assistance suddenly got help paying their premiums.

The enhanced premium subsidies expire in December, and Democrats are refusing to reopen the government until Republicans agree to extend them.

The Republican talking point centers on the classic “taxpayer waste” argument, and that the subsidies in question were never meant to be a long-term benefit of having ACA coverage.

That argument is getting harder to make as their constituents start shopping for insurance next year.

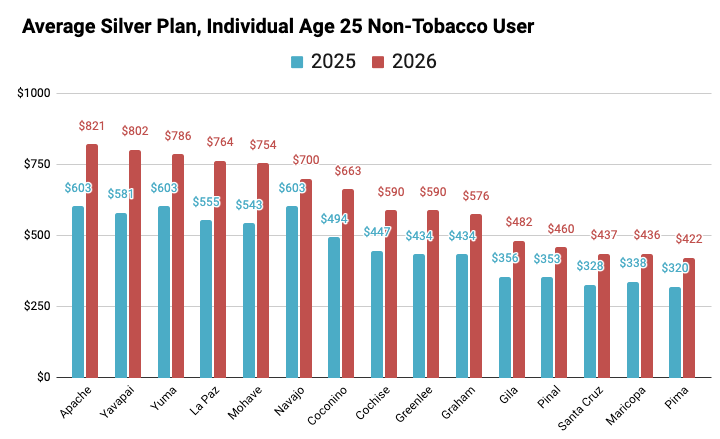

Insurers on Arizona’s ACA marketplace are raising premiums by an average of 34% for 2026, according to federal filings with the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. But monthly premiums depend on a lot of factors, like your age, where you live and how many people are on your plan.

The average monthly premium for a 25-year-old, non-tobacco user living in Maricopa County on a mid-level ACA plan will jump by about $98 next year. A 55-year-old couple under the same circumstances will pay an average $436 more, per data from the Arizona Department of Insurance and Financial Institutions.

But is that what healthcare actually costs, or just what insurers say it costs?

The death spiral

Leslie Plummer, who uses an ACA plan with her husband, said her monthly premium is set to jump from $949 to $2,000. For the last two years, the couple relied on about $900 a month in subsidies.

Plummer’s husband retired after battling prostate cancer, and Plummer left work soon after to care for her 89-year-old father-in-law. They took more out of their retirement savings this year, so she expected to pay a bit more based on that higher income, but not double. If they stick with their ACA plan, most of that extra income will be swallowed by higher premiums now that their subsidies are gone.

“We might just have to do it, and we’re lucky, we could afford it. Most people can’t, “ Plummer said. “But it would still hurt.”

She’s now weighing whether or not to go without insurance, but it’s a more difficult negotiation for Plummer and her husband than those without health complications to worry about.

Plummer’s situation highlights a larger phenomenon experts call the “death spiral” — when healthy people see their premiums spike, they can afford to take the risk and drop coverage. The ones who can’t take that gamble end up footing the bill, because providers raise rates to cover a smaller, sicker pool of people.

But before the market even has a chance to spiral, people like Plummer are already seeing their rates double, partly because insurers are preemptively baking in the impact of the subsidies ending.

Meaning even if Congress renews the subsidies, the healthcare system is already in shock, and rates are going up regardless.

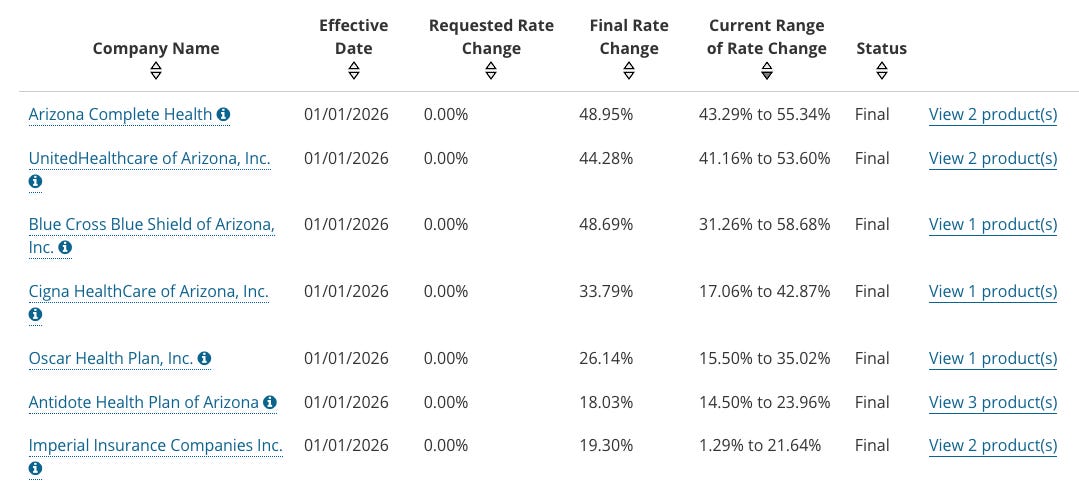

Almost all of the seven companies on Arizona’s marketplace for 2026 cite the incoming loss of those subsidies in their “Consumer Justification Narratives.” When the ACA passed in 2010, it required companies to submit a plain-language explanation of price hikes as part of a more thorough regulatory review.

Arizona’s insurers also cite inflation and increasing medical costs in their justifications, and many also cite the “death spiral” concept. Or as Arizona Complete Health puts in their justification for raising rates by 43% to 55%:

“Emerging trends that indicate the overall health of the insurance pool is worsening.”

But the filings leave out one key motivator behind those price hikes: profit.

There’s a rule within the ACA called the medical loss ratio, which basically says insurance companies have to spend at least 80%1 of the premiums they collect on actual healthcare costs. The other 20% can go to profits and administrative expenses.

The rule, which is meant to keep insurers honest, can backfire. It’s intended to keep insurers from raising premiums for a larger profit, because no matter how much money in premiums they collect, they can only keep 20%.

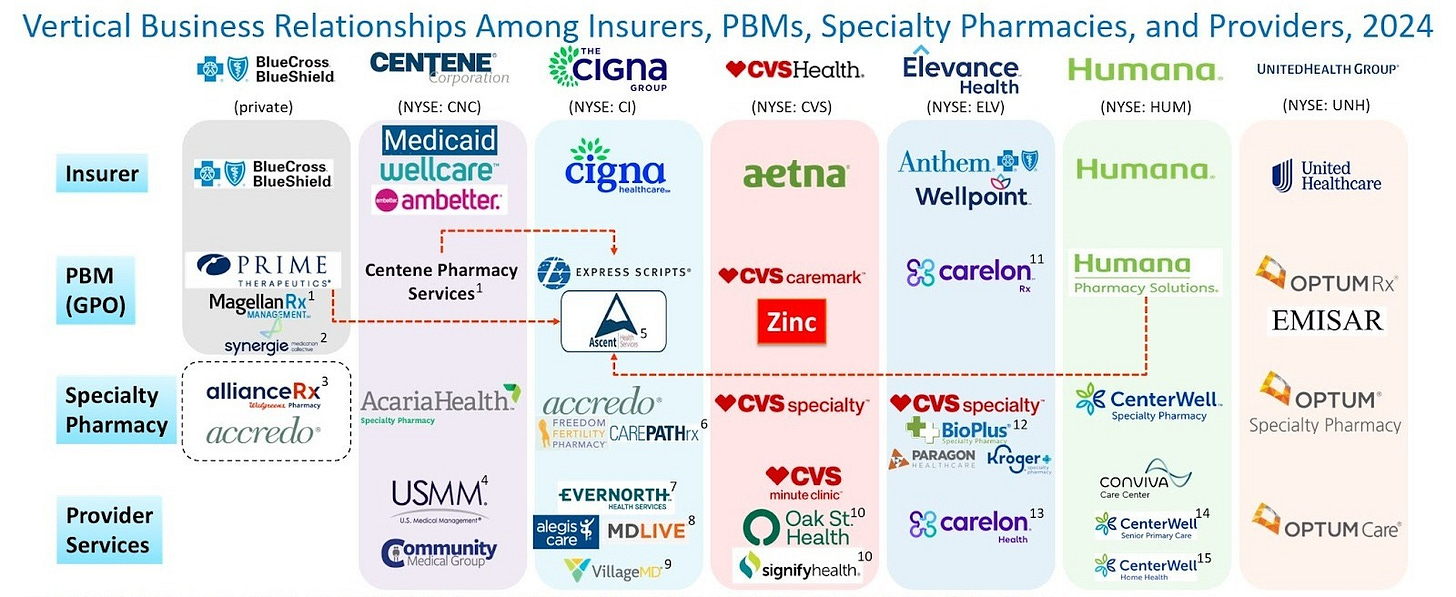

Doctors and hospitals don’t have those same profit restrictions, however. So the insurance companies started becoming the doctors and hospitals.

They bought up the very companies they’re supposed to pay.

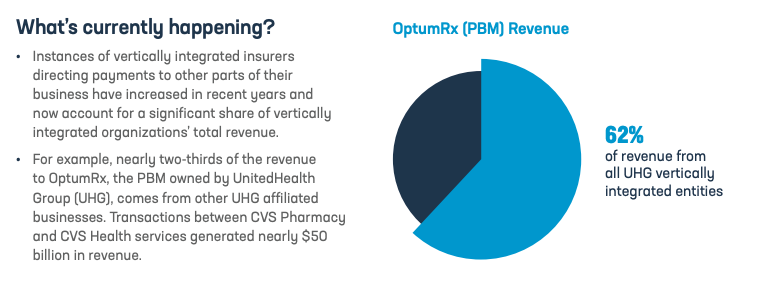

For example, the UnitedHealth Group, which controls a huge chunk of Arizona’s health insurance market, has a non-insurance subsidiary called Optum. As of 2023, Optum reports employing 90,000 physicians.

So when a UnitedHealthcare member goes to the doctor, there’s a good chance they’re seeing a physician employed by the same parent company that insures them. The insurance payout becomes a check that the insurer writes to its own sister company.

On paper, the money looks like it’s being spent on care. In practice, it’s just circulating inside UnitedHealth’s corporate ecosystem in a closed loop.

All that consolidation is also really bad for competition, and with fewer competitors, companies have less incentive to lower costs.

Reader Eric Kurland told us UnitedHealthcare is quoting him for a $2,219 monthly premium through the ACA, or a $20,000 yearly increase from what he pays for a plan with his wife now.

Both Kurland and Plummer currently use Banner/Aetna’s ACA health insurance plan. Aetna — which is owned by CVS — is leaving the exchange next year, leaving about a million people without coverage.

Kurland and his wife are retired teachers, and they got an ACA healthcare plan after retiring two years ago. Since then, he said, “the options are getting smaller, you get less choice and worse coverage each year.”

Kurland’s old plan through Banner/Aetna set him back about $500 a month. Similar to UnitedHealth, Aetna is part of a giant health conglomerate owned by CVS. Banner/Aetna, however, is a joint venture created specifically for Arizonans.

The insurance side (Aetna) and the hospital chain (Banner) share ownership and profits, but remain separate entities. The structure lets Banner benefit from insurance revenues, and Aetna profit from Banner’s patient base.

The company’s pitch was that by merging the payer and provider into one coordinated system, it could control costs and pass those savings along as lower premiums.

Instead, Aetna dropped out of the ACA this year, citing substantial financial losses.

And without the enhanced subsidies next year, less money will flow into the system to help insurers beef up the 80/20 profit pie.

What now?

Some of Arizona’s elected officials are trying to do something about insane healthcare costs.

Gov. Katie Hobbs has implemented medical debt relief programs and prescription savings programs. Attorney General Kris Mayes is holding town halls to hear about health insurance companies denying claims for a potential legal challenge.

Attendees at the first town hall in Gilbert told Mayes that Cigna Healthcare is denying medical insurance claims — one of many issues the attorney general will loop into a larger investigation. Meanwhile, Cigna’s 2026 rates on the ACA marketplace are jumping up to 42% in Arizona.

The state-level moves are a reaction to a larger problem: For years, federal subsidies have made it possible for insurers to profit without most people feeling the pain.

Meanwhile, Arizona’s Republican congressional delegation insists the ACA subsidies were never meant to last; they were just a COVID-era patch.

But is the healthcare system we were meant to return to one where people’s sickness is someone else’s revenue stream?

That is the business model.

The threshold is 85% for large group insurers and 80% for individual and small groups.

Some elements of life (and death) are built for "Socialism". Don't steam up the windows whining about it...use it. Dozens of other countries with superior health care realize everybody gets sick...ergo, insure everybody. That lowers each persons individual liability. Sweat the details later. This is common sense as applied by Econ 101.

Great article Ncole, thank you!