Happy Halloween, readers!

Arizona’s politics can be pretty scary, but the real horrors started a long time ago.

Today, we’re digging into the haunted political origins of Arizona’s territorial capital.

Turns out, Prescott is still hosting lawmakers — they’re just a little bit more transparent.

But first: We have plenty of tricks up our sleeve. Could you spare a treat?

Arizona’s Capitol has plenty of spooky things: disappearing rules, zombie bills and hauntingly long hearings.

But the oldest ghosts in Arizona politics aren’t in Phoenix at all. They’re still wandering Prescott.

More than 160 years ago, Arizona’s first legislative assembly gathered in a floorless hall in Prescott to come up with the territory’s new laws. They managed to write an entire legal code in just 43 days, which puts many modern legislative sessions to shame.

There was (quite literally) a long, winding road to get there, and it claimed a lot of lives before Arizona’s first laws were inked.

Unfortunately, we don’t know anyone who was alive to see the first territorial Legislature in 1864.

But we found a medium who can talk to them for us.

For 15 years, Darlene Wilson has guided curious tourists through the haunted historic buildings in Arizona’s original capital. As a medium, Wilson says she spends a lot of time helping Prescott’s “thousands of spirits” pass on to the other side.

“The whole town is haunted,” she told us.

Cursed origins

The Arizona Territory was born under a bad omen.

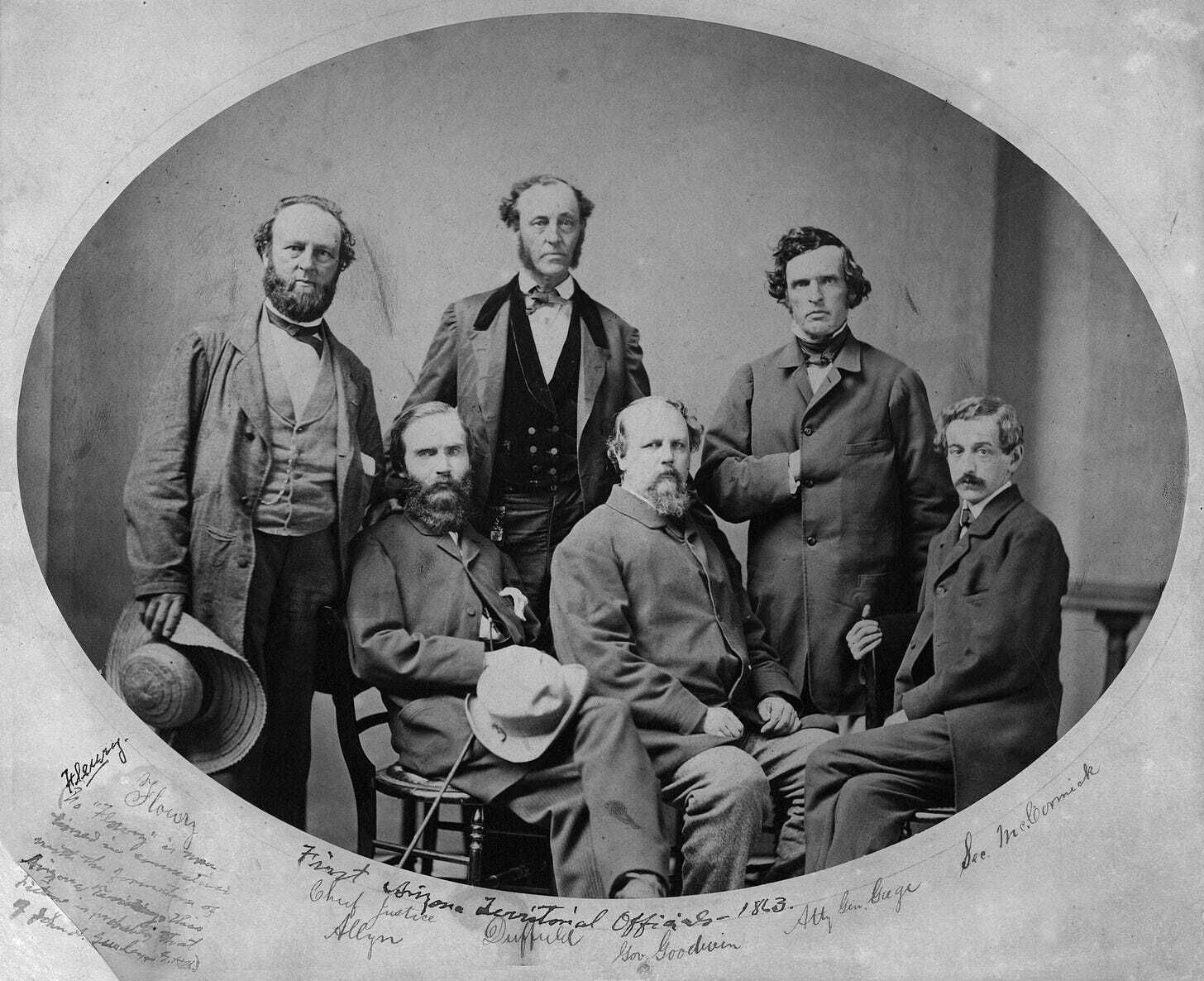

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln named John Gurley as Arizona’s first territorial governor. But the night before he was set to depart for the frontier, Gurley died from appendicitis.

Undeterred by that dark twist of fate, John Goodwin took over as governor and actually made it to Arizona. In 1864, he and a group of settlers set up headquarters at Fort Whipple, which was built during years of bloody clashes between white settlers and the Indigenous people.

Fueled by gold fever, Goodwin wanted Arizona’s capital to be closer to the mines, so he led a group of men into the mountains in an expedition that would claim the first Fort Whipple soldier’s life.

One of the pioneers, Judge Allyn, gave a chilling detail when recounting the death of Private Joseph Fisher.

“This Fisher started from the post, as I learned afterward, with a presentiment he was to die; he dreamed about it, and had talked wildly about it,” Allyn wrote in a February 1864 letter.

While crossing a river, the settlers encountered a group of 15 Native Americans and killed five of them. Fisher was hit by an arrow to his side in the battle.

“He was very much excited, and the wound bled copiously. We dared not open the coat to get at the wound lest the sight of it would make him faint,” Allyn wrote.

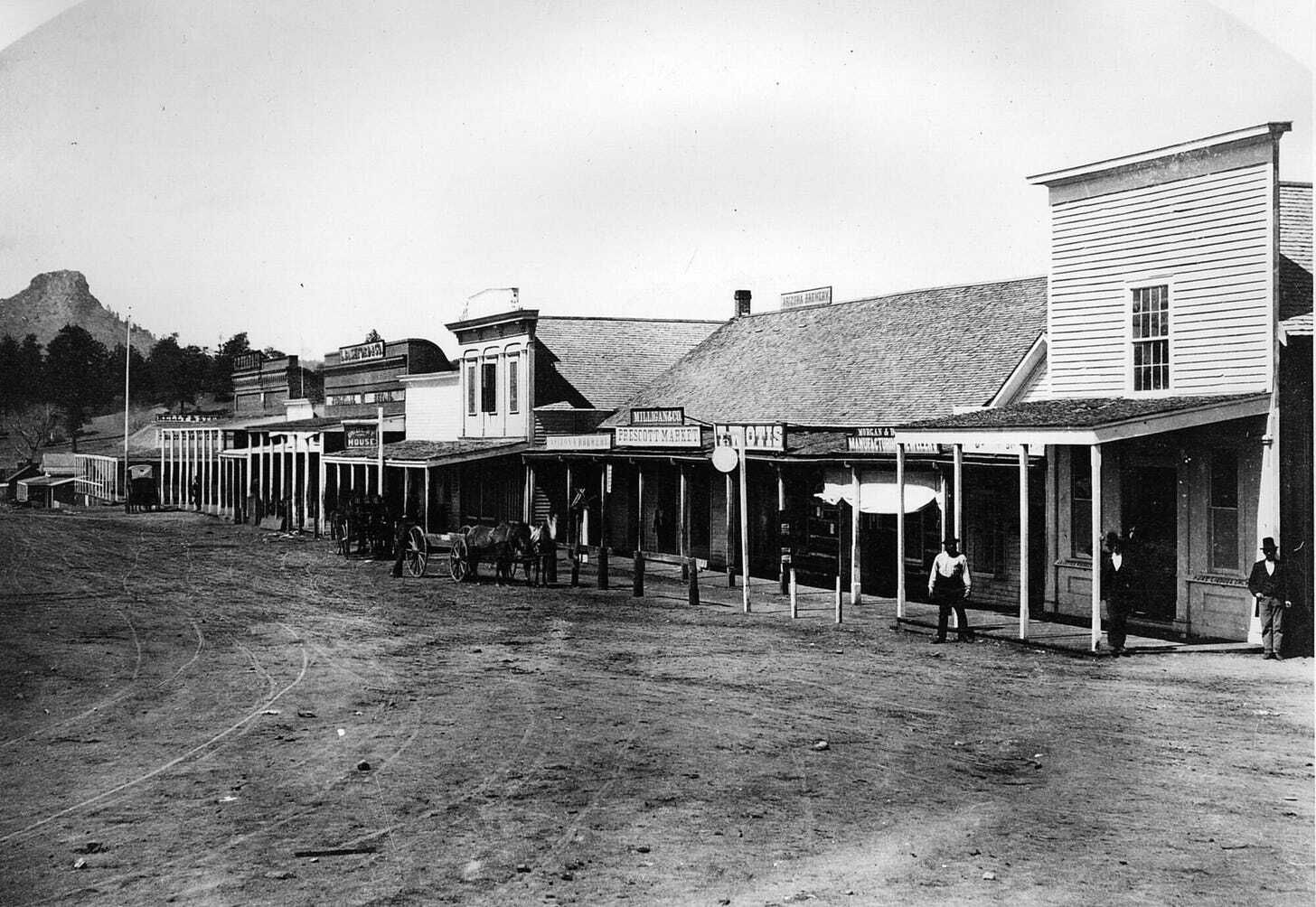

Goodwin eventually decided the new territorial capital should be at Granite Creek, and moved Fort Whipple 20 miles away to the present-day Prescott area. The promise of gold brought a flood of settlers, and with them, plenty of death.

Whiskey, sin and spirits

Territorial Prescott teemed with prospectors and troublemakers, so the city built a courthouse in 1878 to keep the peace — and to punish those who disturbed it.

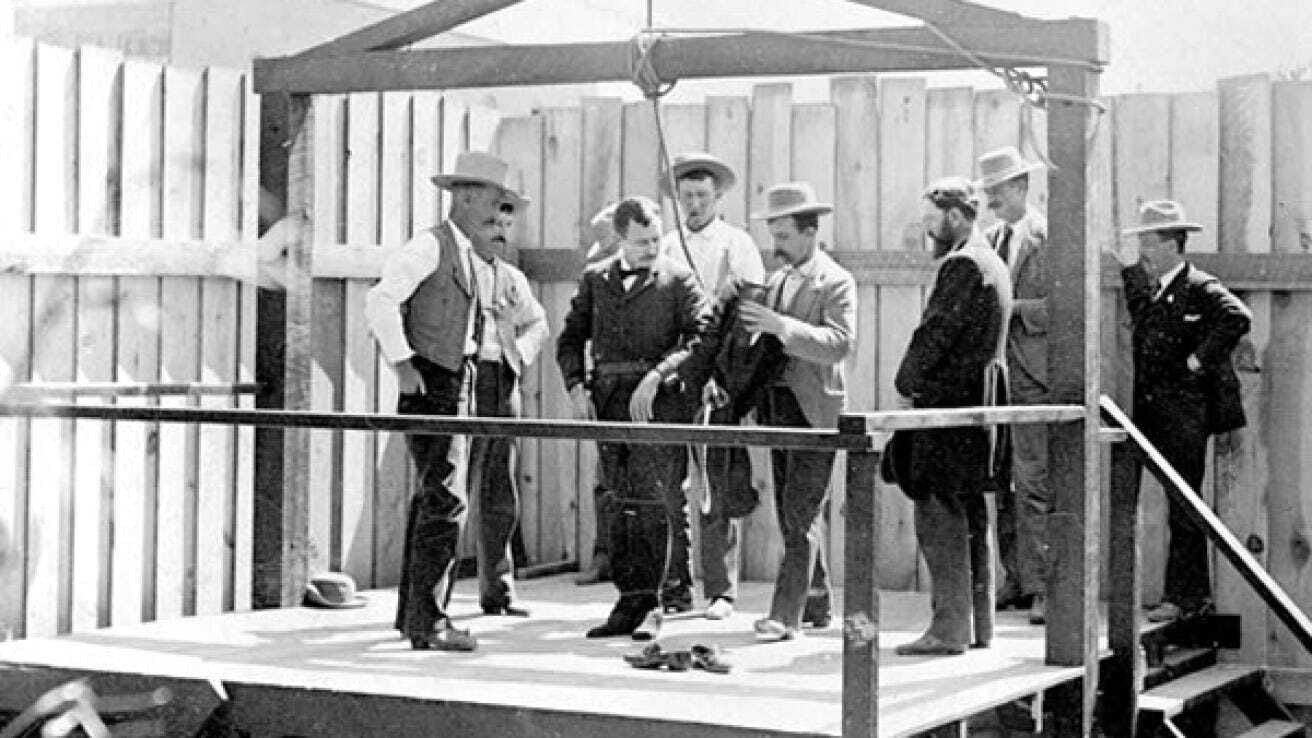

Fleming Parker was one of those peace-breakers. After he was jailed in the courthouse basement for train robbery in 1897, he teamed up with other inmates to overtake the guard, and he shot and killed a popular Prescott attorney on the way out.

Parker then stole the sheriff’s horse and gallivanted throughout northern Arizona for 17 days. After an intense manhunt, which some think was inspired more by the stolen horse than the dead lawyer, he was caught and brought back to Prescott to be hanged.

Before Parker’s hanging, the Tombstone Epitaph documented his last words: “Whenever people say I have to go, I am one that can go.” Parker was declared dead after 10 minutes and 50 seconds.

The same Courthouse Plaza that saw dozens of hangings like Parker’s is now one of the stops on Wilson’s paranormal tour, where she says she feels a lot of ghostly, historical energy.

The last hanging at Courthouse Plaza was in 1903, and Wilson said tour-goers often capture photos with orbs of light in front of the courthouse — signs that the spirits are still hanging around.

But the most haunted place on Wilson’s tours is across the street from the courthouse: The Palace Saloon, one of Arizona’s oldest bars.

Built in 1877, it became one of over forty bars in Prescott’s “Whiskey Row,” a historic block that earned its name from its prevalence of liquor.

Barry Goldwater, the face of Arizona conservatism, regretted not buying the bar when he had the chance. In a letter to a friend, Goldwater wrote about a Palace Saloon story he heard “involving the movement of the capital to Phoenix.”

It’s a pretty famous legend.

“As you know, the second floor was a house of prostitution. I think the original brass beds are still up there as well as the bedpans, cuspidors, etc.,” Goldwater wrote. “The story is that the leader of the Senate, having one glass eye, had it stolen during the night. As a result, he couldn’t take his place in the Territorial Senate (the next day) and the lack of his vote sent the capital to Phoenix.”

Beyond distracting politicians with its working girls, the Palace Saloon doubled as a polling place — and, many times, a crime scene.

Wilson said she’s had to clear the Palace Saloon of “some very unsettling ghosts” several times. She’s even cleared the homes of saloon employees who took home bar artifacts they didn’t realize came with company.

The bar’s employees told Wilson they’ve had the stays pulled out of their corset uniforms, and several women reported being attacked in the bathroom.

“When I’ve done clearings in there, the (ghosts of) men always line up first, and they kind of shove the women into the back,” Wilson said. “Back behind the Palace Saloon was the red light district, and it went on for blocks. So a lot of the women that we see in there were prostitutes, but they weren’t ill-thought of back then, because it was a profession, it was legal, and some of the women, that was the only way they had to survive.”

But many of them did not survive.

Jennie Clark was beaten to death by her lover, Fred Glover, inside the Palace Saloon.

Governor Frederick Tritle commuted Glover’s sentence from death to life in prison, and after several more appeals, Glover was released in 1890 and never heard from again — at least while he was alive. Some believe he’s still carrying out his sentence in the saloon.

Discovery’s “Ghost Adventures” crew visited the Palace Saloon in 2016, and posited that a loud thump sound was a spectral replay of the fatal beating.

Prescott’s pets

Prescott’s ghosts aren’t all rowdy cowboys. In fact, some of its most popular haunters are very good boys.

To help meet the increased housing demand of post-territorial Prescott, Rancher J.B. Jones built Hotel Vendome near Whiskey Row in 1917. Many summer tourists stayed through winter to recover from tuberculosis, but according to local legend, some never left.

Room 16 of Hotel Vendome is said to be haunted by Abby Byr and her cat, Noble. As she suffered from tuberculosis, her husband left to get help and never returned, and she starved herself to death.

Some think Byr is still waiting for her husband’s return — guests report an apparition of a woman roaming the halls. And several hotel guests, including Wilson, reported feeling a cat brush against them.

To help a guest staying in room 16 summon Noble, Wilson gave her a saucer of milk.

“The next morning, she comes downstairs, she’s so excited,” Wilson said. “She said she woke up at 2:30 in the morning to this cat kneading her shoulders.”

A few blocks away from the hotel, another four-legged legend is said to roam the courthouse plaza.

Wilson said that around 1942, Whiskey Row patrons would order two steaks — one for them, and one for the community dog, Mike.

Before she knew about Mike’s story, Wilson said she recorded a dog barking and someone calling “Here, Mike!” in one of her investigations.

No one knows how Mike came to town, but everyone loved him. And when he died in 1960, the community memorialized him with a plaque that still sits in the square’s northwest corner. It reads:

“Regardless of age, color, creed or station in life, he was a silent, tolerant, loyal friend … take heed if you will; a moral lies herein.”